Background and Research Expertise

Dr. Lilly Parker at the airport in Anchorage, posing with a taxidermied polar bear, and thinking about how Unangan ancestors may have responded to the presence of bears in Unalaska. Photo credit: C.F. West.

Dr. Lilly Parker is a research scientist at the Laboratories of Molecular Anthropology and Microbiome Research (LMAMR) at the University of Oklahoma where she focuses on ancient DNA, mammalian diversity, conservation genomics, and human-mammal relationships. Her work in the Arctic began during her NSF Office of Polar Programs postdoctoral fellowship at LMAMR where she worked to understand the mysterious presence of polar bears in Unalaska, Alaska approximately 5,000 years ago. She notes that this work expands upon Dr. Catherine West’s Unalaska Sea Ice project at Boston University, which examines the environmental and cultural impacts of Aleutian Island neoglacial periods.

Parker’s academic background and training lies in population genetics and systematics of mammals, specializing in ancient DNA laboratory methods and bioinformatics. She completed her dissertation at the Center for Conservation Genomics (CCG) in the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, where the interdisciplinary environment exposed her to a broad range of research approaches. After her doctoral work, Parker sought out opportunities to integrate an anthropological perspective into her work that explores the intricate and dynamic relationships between humans and their environments—particularly human interactions with other mammals. She explains that collaborating with her mentors, Dr. Catherine West and Dr. Courtney Hofman, has allowed her to develop a holistic understanding of the significance of the presence of bears in Unalaska by weaving together cultural, ecological, and genetic components.

Dataset Highlight

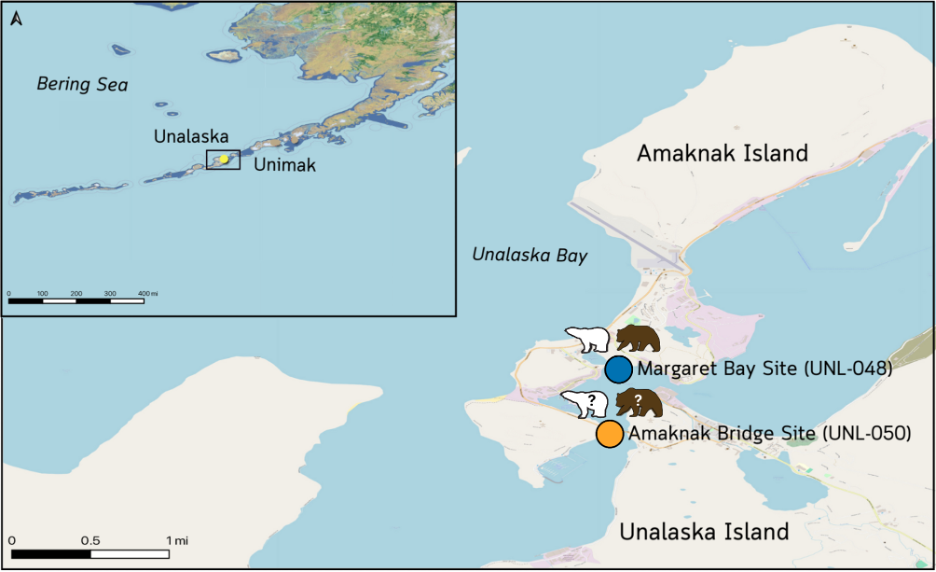

Map highlighting the positions of two archaeological sites: Margaret Bay (ca. 4700 rcyr BP) and Amaknak Bridge (ca. 2500 rcyr BP). Bear icons indicate possible bear remains at Margaret Bay and an unidentified bear species at Amaknak Bridge. From Parker et al., 2025.

Giving context to the project, Parker explains that in the early 2000s, archaeologists uncovered bear remains at two sites on Unalaska island: Margaret Bay and Amaknak Bridge. These discoveries were both surprising and significant given the absence of paleontological or historical records of bears inhabiting Unalaska. The island lies approximately 500 miles south of the historically documented southernmost range of polar bears and about 60 miles west of Unimak Island, where the nearest existing brown bear population exists. The remains, estimated to be between 4,700 and 2,500 years old, may suggest that sea ice reached the Aleutian Islands during the Neoglacial period, a time marked by cooler conditions compared to the temperate climate of the region today. Parker notes that “this finding is especially intriguing because there is no documented history of Unangax̂ (Aleut) communities, who have lived in the Aleutians for at least 9,000 years, hunting or utilizing bear products”.

The goal of the project is to use zooarchaeological methods to determine whether the uncovered bear remains belonged to polar or brown bears, which Parker notes is a difficult distinction because their skeletons are so similar. She explains that identifying species and understanding the context of their presence can shed light on past climate conditions and determine how they impacted the complex relationships between humans, animals, and the environment.

This collaborative research involved publication of a dataset at the Arctic Data Center:

- Lillian Parker. (2024). A zooarchaeological analysis of bear (Ursus spp.) remains from two archaeological sites in Unalaska, Alaska (4700 BP – 2500 BP). Arctic Data Center. doi:10.18739/A25T3G219.

And an associated publication in Nature Scientific Reports:

The study confirmed the presence of both polar and brown bears at the Margaret Bay site, with age profiles and butchery patterns suggesting that the bears were harvested locally. Parker explains that the expansion of sea ice during the Neoglacial period likely facilitated the movement of polar and brown bears to the Unalaska region. While species identification was confirmed for a portion of the recovered bones through morphological analysis, further efforts are underway to analyze DNA sequence data. This genetic analysis aims to determine the species of the remaining specimens and identify the modern populations to which these bears are most closely related.

Methods and Impact

Dr. Catherine F. West working in the collections at the Museum of the Aleutians with the Executive Director Dr. Virginia Hatfield. Shown are harpoon toolkits used by Unangan ancestors for hunting on the open water. Photo credit: L. Parker.

The team used zooarchaeological methods that included comparative morphology, assessment of butchery patterns, and age estimation. Parker further explains that ancient DNA sequencing is currently allowing for sequencing and analysis of mitochondrial and nuclear geonomes to determine bear species and population, relatedness among individuals, effective population size, and demographic trends.

The overarching goal of the project is to understand the environmental and cultural impacts of neoglacial cooling in Unalaska. Parker’s role is providing a lens into the context and implications of the presence of butchered bear remains in archaeological contexts, aiming to understand how humans were interacting with bears and how the bears themselves were affected. She explains that “… in many regions where polar bear and brown bear ranges have overlapped, the two species hybridized… this could have occurred on the Alaska Peninsula as well”.

When asked about the most exciting part of the project, Parker found it difficult to choose just one. She explained how privileged she felt to work with remains that are a part of Unangan cultural heritage: “The bear remains are exciting to local community members because the presence of huge terrestrial carnivores like bears in Unalaska is difficult to imagine”. She reported that the best part of the research so far was traveling to Unalaska and meeting with community members, as well as teaching students at Camp Qungaayux what they have learned about bears and about the methods they used to come to their conclusions.

A Love for Collaboration

Kaylee Tatum teaching “the Mystery of the Margaret Bay Bears’, a lesson describing the results of this research that she developed with Dr. Parker, at Camp Quanayuux, the Unangan summer culture camp. Photo credit: L. Parker.

Parker has a deep love for mentoring students, doing public outreach events, and working with her collaborators, stating that she “loves being a part of the journey of discovery and learning”. In fact, when asked what advice she would give to young scientists or students interested in pursuing a career in Arctic research, Parker advised choosing the best group of collaborators you can find. She emphasized the joy she gets from working with a group of dedicated professionals who all get to learn from each other. While Parker brings a background in population genetics, systematics, and ancient DNA of mammals, her collaborators bring expertise in zooarchaeology, cultural and molecular anthropology, and chemical ecology. By combining these perspectives and working in interdisciplinary teams, Parker says the group can “piece together a much more complete picture than any one discipline could provide on its own”.

Written by Nicole Greco

Community Engagement & Outreach Coordinator