Background and Research Expertise

Dr. Schmidt hosting a table at a community wildfire event in May 2022.

Dr. Jen Schmidt grew up in the Lower 48, but from an early age, watching the morning news and national weather reports sparked a fascination with Alaska and a long-held desire to travel there. After double majoring in ecology, evolution, and behavior and genetics and cellular biology at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, Schmidt used her graduate education as a gateway to Alaska. With a passion for impactful interdisciplinary research, Schmidt pursued a Ph.D. in wildlife biology at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, focusing on the social and ecological influences on the genetic structure of Moose. While this project combined Schmidt’s love for fieldwork and labwork, she quickly realized an important component of the work—humans, especially those interested in moose hunting and management. Throughout graduate school, Schmidt fell in love with Alaska and decided to stay and do research in the place she’s most passionate about.

Schmidt is now an Associate Professor of Natural Resources Management and Policy at the University of Alaska Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research, where she studies the human dimensions of wildlife, natural resource management, and ecosystem services, and uses tools such as geographic information systems (GIS) and modeling. We met with Schmidt to learn more about their work in wildfire management and hazardous fuels.

Dataset Highlight

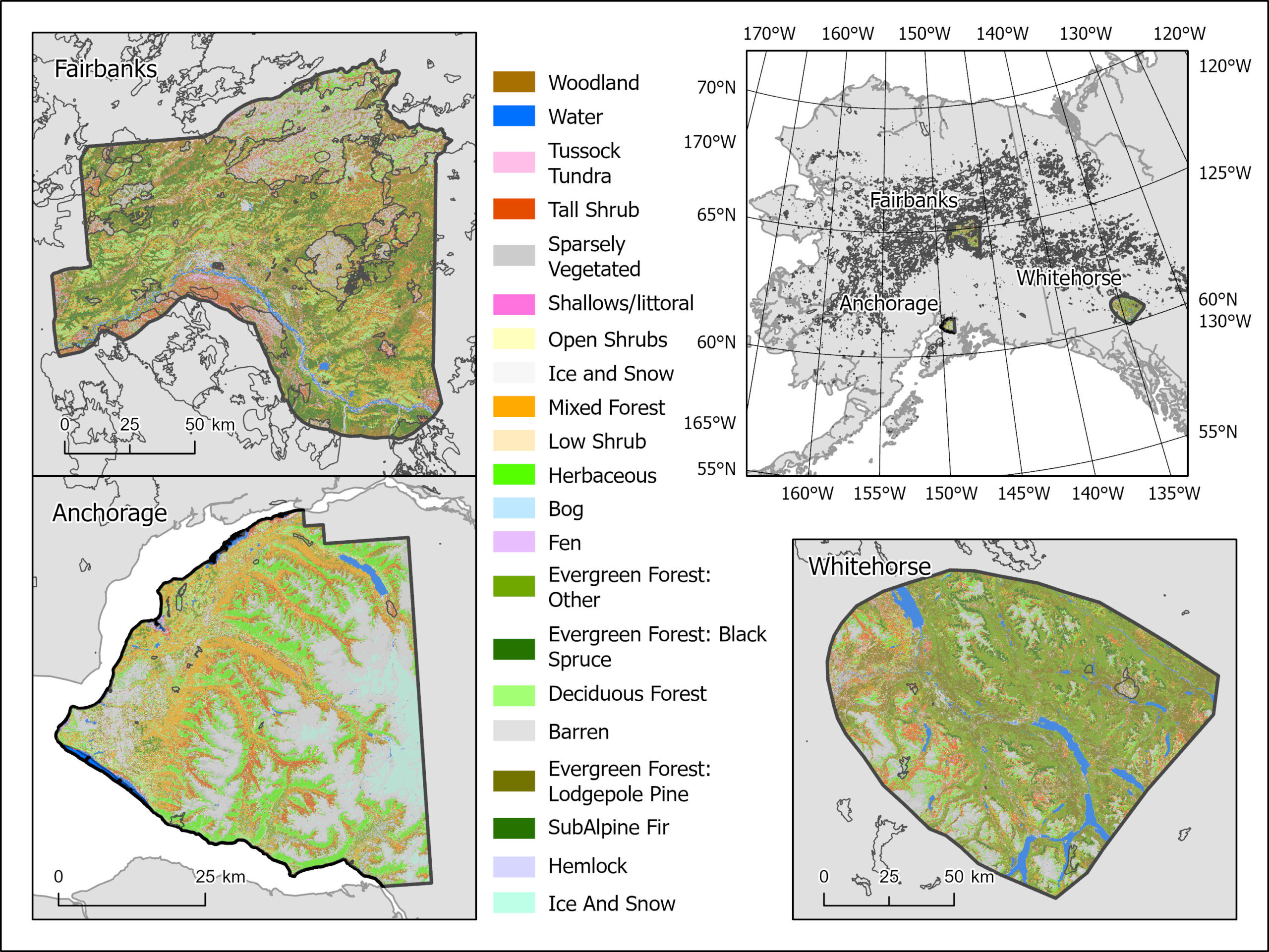

Illustration of the three study areas where wildfire hazard and exposure maps were created and the base vegetation.

In general, Schmidt’s research is highly adaptable and responsive to community needs, both for residents and agencies. With a background in resource management, she specializes in blending environmental work with social issues. As a resident of Anchorage, along with 40% of Alaska’s population, Schmidt recognized the need for locally developed products to inform science-based decisions. Having lived in both Fairbanks and Anchorage, she noticed many homes with highly flammable spruce trees located nearby. Schmidt notes that despite the risk, many communities have outdated Community Wildfire Protection Plans (CWPP), including her home town of Anchorage, which was from 2008. To effectively inform these plans, risk maps need to be regularly updated, and Schmidt’s collaborative research is helping do just that.

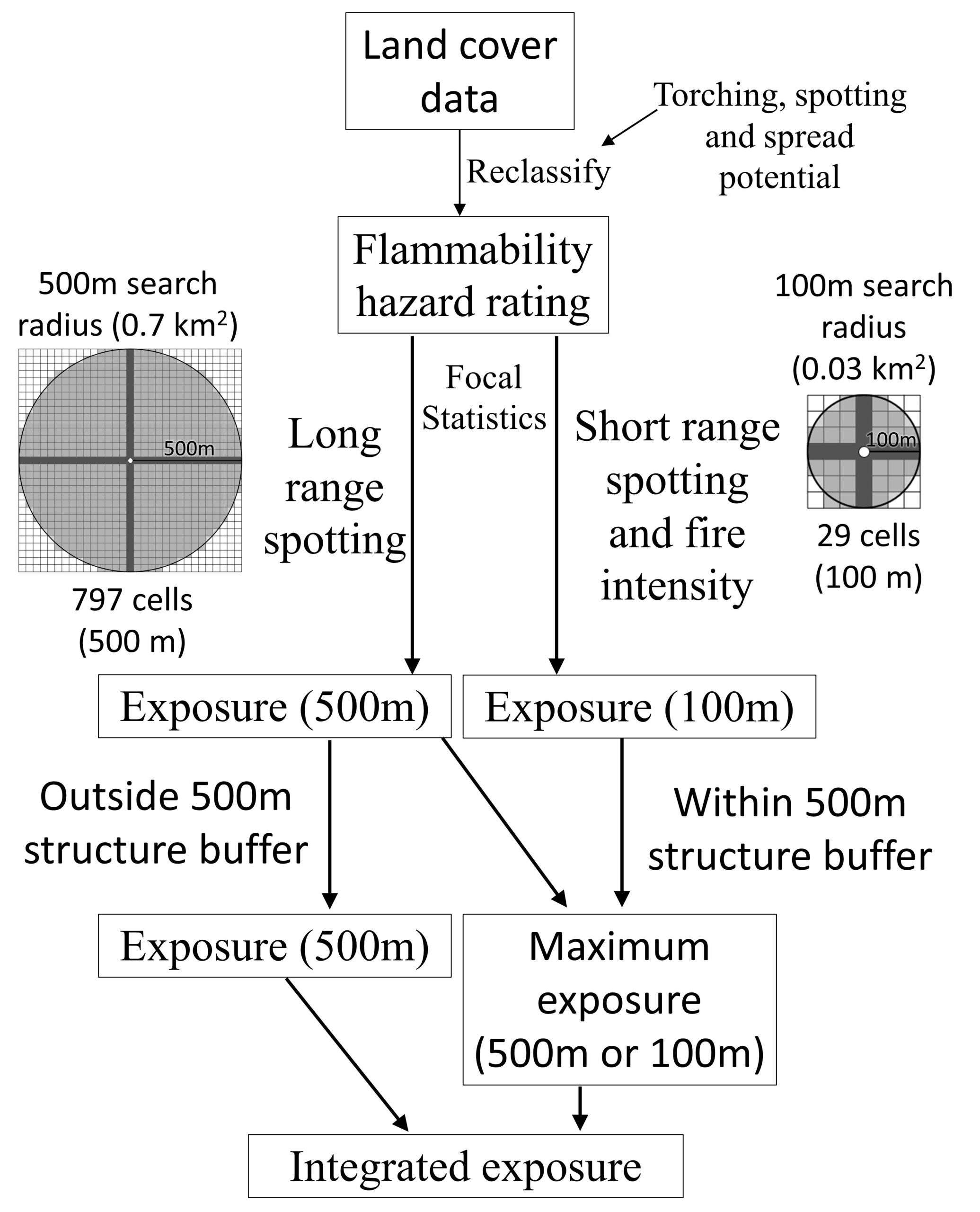

Overview of the methods used to create wildfire exposure maps, which include the creation of hazardous fuels.

This project resulted in the creation of the Hazardous Fuels: Anchorage and Fairbanks, Alaska and Whitehorse, Yukon 2014-2054 dataset, authored by Jennifer Schmidt, Zeke Ziel, Monika Calef, and Anna Varvak, and published on the Arctic Data Center.

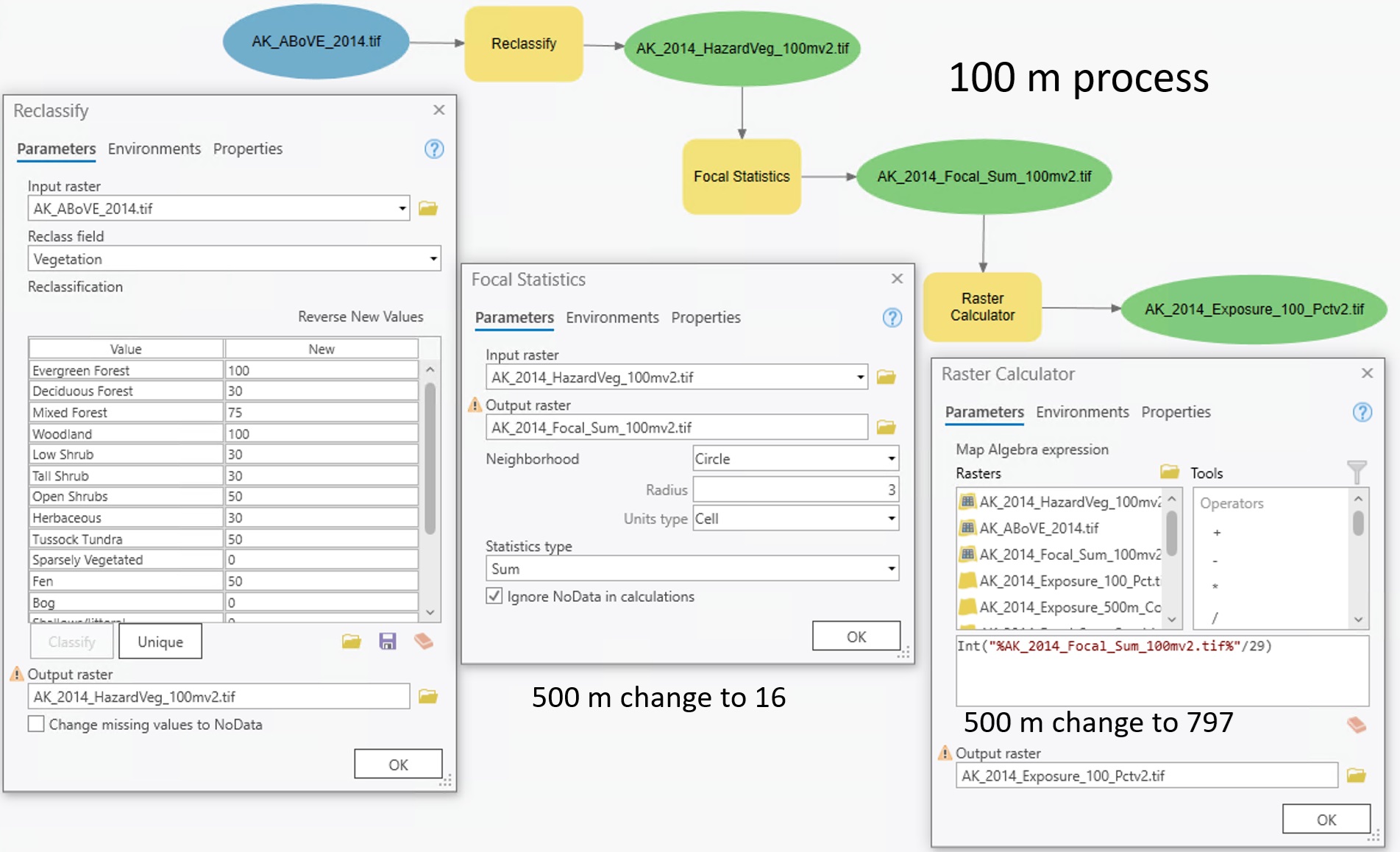

The dataset is based on NASA’s Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE) annual landcover layer from 1984-2014 and builds upon the foundational work of Jennifer L. Beverly (University of Alberta) and others. The landcover classes enabled the team to assign a flammability score, which allowed for analysis of fire risk and ember dispersal. ArcGIS and zonal statistics were used to calculate average flammability within specific regions, combining remote sensing data with ESRI tools to develop detailed map products.

Shows the tools used to create hazardous fuels and wildfire exposure maps.

Flammability hazard, or hazardous fuel, refers to vegetation that has the potential to ignite and cause damage, loss, or harm to people, infrastructure, equipment, natural resources, or property due to its flammability. With expert guidance from the Alaska Fire Science Consortium team and incorporation of the Alaska Fuels Guide, Schmidt’s team was able to determine the flammability of 15 classes of Arctic vegetation. Community feedback was vital in fine-tuning techniques, deciding on map scales, and the ultimate application of the maps.

Supporting Arctic Communities Through Wildfire Risk Maps

Undergraduate at the University of Alaska Anchorage shows early wildfire exposure maps to residents.

Wildfires are an increasing concern for Arctic communities, but Schmidt notes that traditional national datasets often perform poorly in Alaska. Much of the national fire data assumes that vegetation returns to its pre-burn state after just ten years. In Alaska, this assumption is not accurate. Additionally, these datasets are often difficult for communities to access or interpret due to their size and complexity. Understanding them typically requires extensive background knowledge and significant computing power, putting this information out of reach for many local decision-makers.

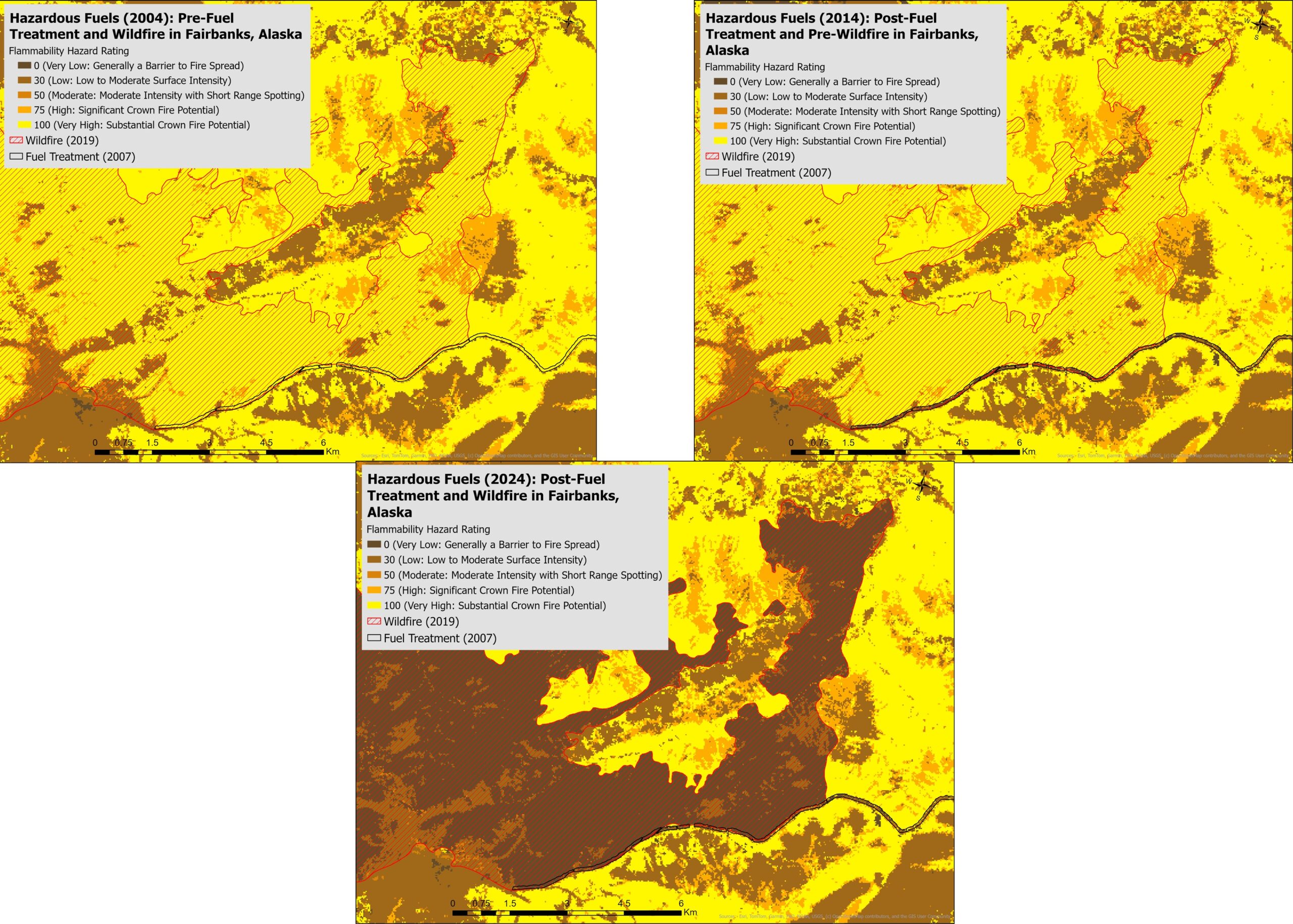

To address this gap, Schmidt’s team began by developing wildfire risk maps in Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Whitehorse. This product can be changed on the fly to adapt to community needs (like adding different fuel types). The dataset has proven valuable in many ways. The State of Alaska has adopted the maps to guide planning and create CWPPs. Communities often request customized maps to help plan fuel treatments, evaluate evacuation routes, and identify hazardous vegetation that could carry fires into populated areas. By adapting Jennifer Beverly’s methodology for use in Alaska, Schmidt’s team conducted vulnerability analyses to provide communities with deeper insights into wildfire risks. The maps also allow planners to evaluate the effectiveness of fuel treatments, which can be used to track how mitigation funding is being used and assess how long wildfire hazard and risk.

Surprising Findings

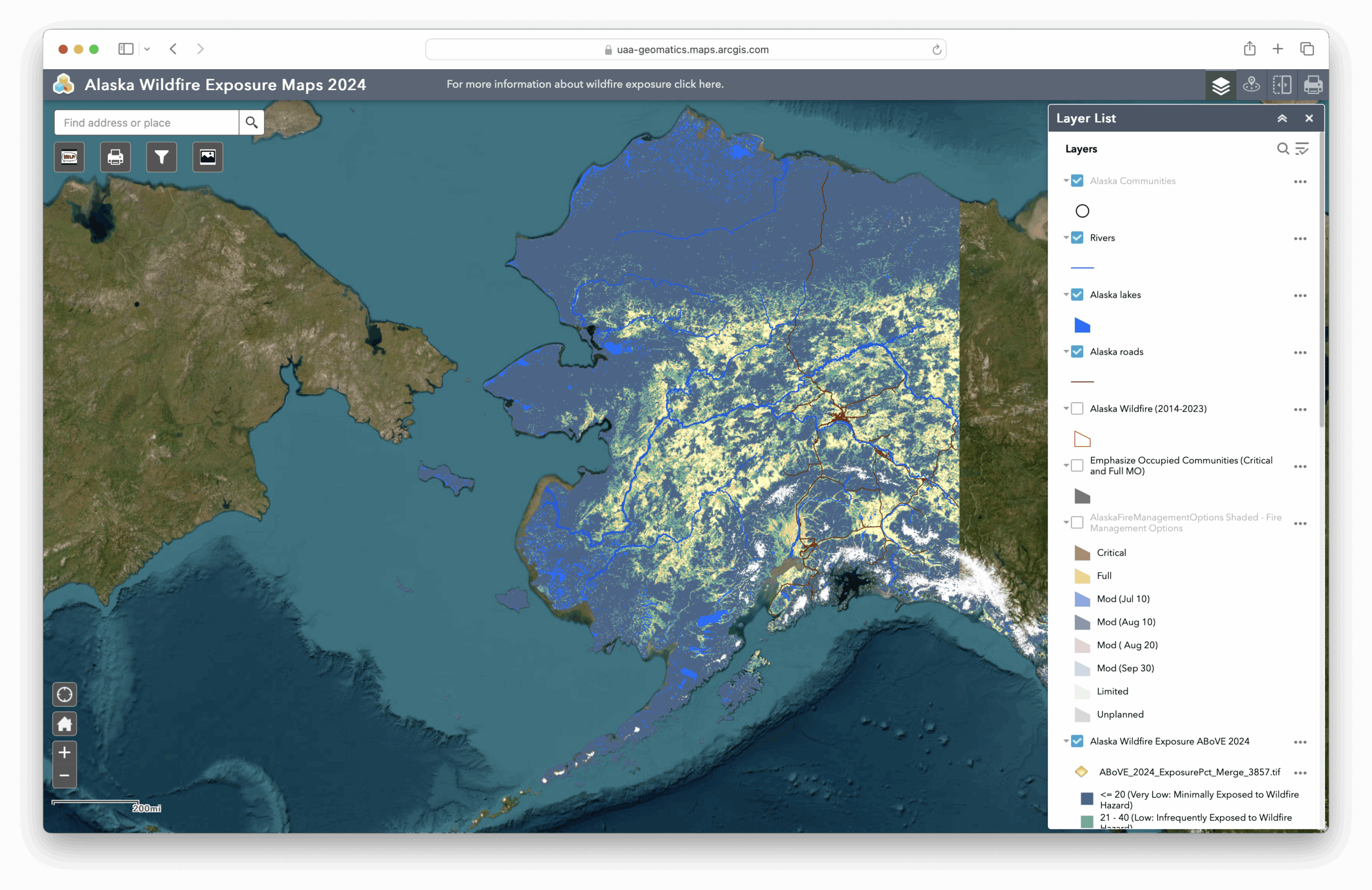

2024 Alaska Wildfire Exposure Maps.

One of the greatest surprises for Schmidt and her collaborators was the success of the Alaska Wildfire Exposure Map. The map revealed areas with high wildfire exposure were in fact more likely to burn, which challenged a prior assumption that burn probability did not reliably predict where fires actually occur. However, these maps performed so well in community applications, that the research is now expanding to include tundra areas.

This map integrates various data layers, including hazardous vegetation and fuels, wildfire exposure, vegetation data, ecosystems, and landscapes to support community-level decision making. As Schmidt noted, it has helped communities, land managers, and researchers use historical fire data to help identify areas that are more likely to burn, which has supported preparedness planning and risk mitigation. For more information, explore the Alaska Wildfire Exposure Maps 2024 on ArcGIS.

Emerging Fire Risks Across Alaska’s Landscapes

Illustration of how hazardous fuels capture fuel treatments and wildfire activity outside of Fairbanks, Alaska.

In 2022, tundra areas in Bristol Bay experienced more burning than in the previous 70 years, highlighting a key realization for Schmidt: more landscapes are flammable than we previously assumed. Wildfire risk is not limited to the boreal forest, and tundra ecosystems are increasingly vulnerable as fire behavior changes across Alaska.

Currently, there is a major gap in comprehensive information on structure (ile. building) vulnerability, particularly data that accounts for the building materials and other components that could influence how homes burn. Schmidt notes that since there is no standardized system to categorize structures and their value, this presents a challenge for accurate risk assessment and supporting community preparedness efforts.

Additionally, Schmidt noted there is an increased need for updated annual land cover data to better assess vulnerability across Alaskan communities. As mentioned, her team has heavily relied on NASA’s ABoVE data, but their maps have not been updated in recent years with the same level of detail or geographic coverage. To help address this gap, Schmidt has built upon existing documentation to further inform the Alaska Wildfire Exposure Maps, and has developed a small-scale vegetation model that can become more scalable, sustainable, and impactful for broader community use.

Why This Work Matters

Building trust is foundational for any successful collaboration when working between communities and scientists, and watching that trust grow over time has been incredibly rewarding for Schmidt. Community members regularly turn to her team as a trusted source of knowledge and resources, given both their research and broader community work. Schmidt describes herself as a public servant, noting this is the central reason why she does this work. She actively encourages the public to reach out, whether it is by text, call, or email to ask questions or seek advice, and emphasizes she’s happy to help.

Preparing for a Career in Arctic Science

“Capitalize on available opportunities as early as you can in your academic career” was the overall message shared by Schmidt. She encouraged undergraduate students to not shy away from the more challenging courses or skills, but rather to seek out the classes that will build strong technical foundations. Schmidt emphasized the importance of developing hard skills ranging from statistics to data management as early as possible, highlighting that these skills not only prepare you for a career in science, but particularly Arctic research.

How the Arctic Data Center Supports Science and Scientists

Participants of an Arctic Data Center data science training course, including Jen Schmidt.

The Arctic Data Center has long supported Arctic scientists in developing their data science skills through our hands-on training opportunities, and Schmidt serves as an example of the effectiveness of our teaching models. In August 2018, she participated in an early iteration of our courses, which had a mixed focus in R and Git/Github called Arctic Data Center Training. She has since expressed appreciation for the experience to learn and regularly encourages many of her graduate students to apply and attend our data science training events when possible.

Schmidt also noted that archiving her data at the Arctic Data Center has extended the reach and impacts of her research, while helping her discover other datasets relevant to her work. In particular, she highlighted an existing dataset focused on North Pacific and Arctic marine vessel traffic as a game changer. Noting that access to well-documented, discoverable data allows scientists to see what work has already been done and to further build on it rather than duplicating it. She credits the Arctic Data Center team for supporting these efforts and hopes they can continue to contribute impactful research in the Arctic research community.

Written by Nicole Greco and Angie Garcia

Community Engagement and Outreach Coordinators