By Natasha Haycock-Chavez, Amber Budden and Matt Jones

At its foundation, open-science is based on making all aspects of scientific research accessible across broad communities, whether professional, academic, or public. This includes publications, data, software, samples, and code, and at its core, open science is built on principles of transparency and capacity for collective knowledge. The practice of open science is being increasingly adopted by researchers across disciplines. There are organizations and working groups such as FORCE11 that promote and support this through development of principles and guidelines that inform research activities. Open-science affords researchers the opportunity to extend the reach of their work (Puebla & Lowenberg, 2021) and increase transparency and public trust, however, such transparency creates challenges for researchers working with sensitive data and Indigenous knowledge. Western knowledge concepts largely inform open science principles and do not consider Indigenous data sovereignty and Indigenous Knowledge (Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group, 2019).

The FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reproducible) principles for data management are widely known and broadly endorsed. They place emphasis on machine readability, “distinct from peer initiatives that focus on the human scholar” (Wilkinson et al., 2016) and as such, do not fully engage with sensitive data considerations and with Indigenous rights and interests (Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group, 2019).

In contrast, the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance (Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, Ethics) developed through the Global Indigenous Data Alliance reflect the human side of data, and ask researchers to put human well-being at the forefront of open-science and data sharing (Carroll et al., 2021; Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group, September 2019).

Indigenous data sovereignty and considerations related to working with Indigenous communities are particularly relevant to the Arctic. With an Indigenous population double that of Indigenous peoples across the globe, there are over 40 different ethnic and cultural groups in the Arctic (Arctic Council, 2021). Many are actively engaging in dialogue on ethical research practice, calling for greater participation in scientific research, and publishing recommendations and guidelines, such as the CARE Principles.

The FAIR and CARE principles are viewed by many as complementary: CARE aligns with FAIR by outlining guidelines for publishing data that contributes to open-science and at the same time, accounts for Indigenous’ Peoples rights and interests. Sharing sensitive data introduces unique ethical considerations, and FAIR and CARE principles speak to this by recommending sharing anonymized metadata to encourage discoverability and reduce duplicate research efforts, following consent of rights holders (Puebla & Lowenberg, 2021). While initially designed to support Indigenous data sovereignty, CARE principles are being adopted more broadly and researchers argue they are relevant across all disciplines (Carroll et al., 2021). As such, these principles introduce a “game changing perspective” for all researchers that encourages transparency in data ethics, and encourages data reuse that is both purposeful and intentional and that aligns with human well-being (Carroll et al., 2021). Hence, to enable the research community to articulate and document the degree of data sensitivity, and ethical research practices, the Arctic Data Center has introduced new submission requirements.

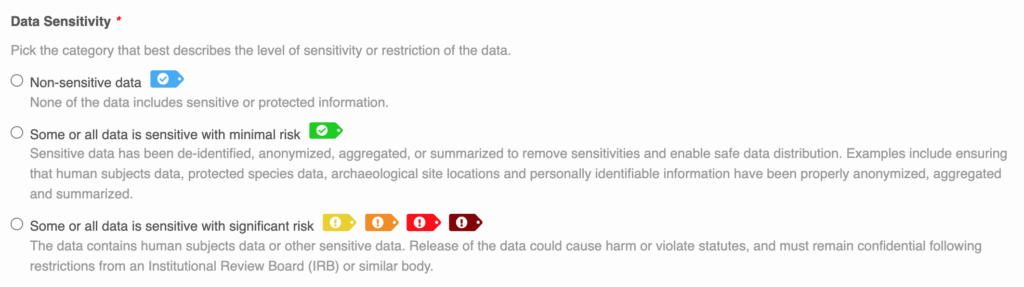

As the primary data repository for the National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs Arctic Sciences section, the Arctic Data Center accepts data from all disciplines including social science and other research that may be subject to IRB restrictions, involve Indigenous knowledge, or have been carried out on Indigenous lands. Researchers submitting data now have the opportunity to articulate these and other considerations as part of the metadata record. First, researchers can identify the level of sensitivity that best represents the dataset from one of three sensitivity data tags ranging from non-confidential information to maximally sensitive information (Figure 1). Based on the level of sensitivity, guidelines and next steps for data submission are provided.

The first tag, “non-sensitive data”, represents data that does not contain potentially harmful information, and can be submitted without further precaution. Data or metadata that is “sensitive with minimal risk” means that either the sensitive data has been anonymized and shared with consent, or that publishing it will not cause any harm or damage to participants. The third option, “some or all data is sensitive with significant risk” represents data that contains potentially harmful or identifiable information, and the data submitter will be asked to hold off submitting the data until further notice. In the case where sharing anonymised sensitive data is not possible due to ethical considerations, sharing anonymised metadata still aligns with FAIR principles because it increases the visibility of the research which helps reduce duplicate research efforts. As with data, it is important to ensure that the metadata being shared is done so with consent from participants, and in alignment with the CARE principles fully.

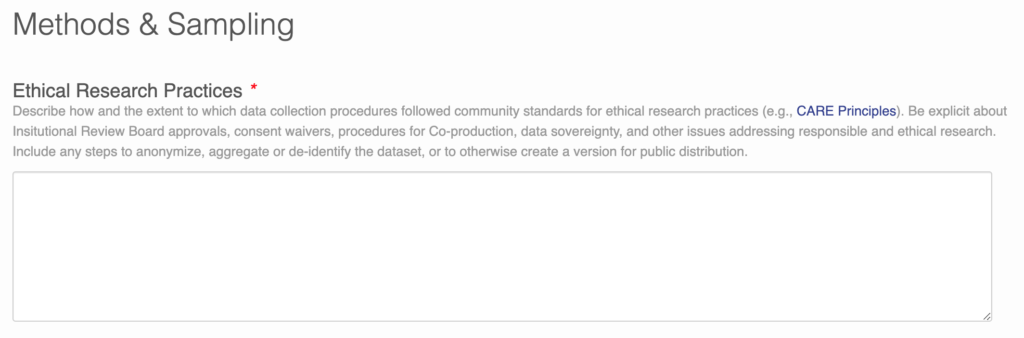

In addition to data sensitivity tags, the Arctic Data Center data submission process now requires data researchers to share the ethical data and research practices present in their research as part of the Methods and Sampling section (Figure 2). This response will form part of the publicly accessible metadata.

Transparency in data ethics is a vital part of open science. Regardless of discipline, various ethical concerns are always present, including professional ethics such as plagiarism, false authorship, or falsification of data, to ethics regarding the handling of animals, to concerns relevant to human subjects research. Sharing ethical practices openly, similar in the way that data is shared, enables deeper discussion about data management practices, data reuse, sensitivity, sovereignty and other considerations. Further, such transparency promotes awareness and adoption of ethical practices.

As the Arctic Data Center embarks on its seventh year, we reflect on the ethical data principles and guidelines that continue to influence and inspire the way in which we manage and curate data. Community developed principles such as CARE and FAIR will continue to inform how we think about data, we will remain responsive to community input and emerging best practices. These topics will be included within future short course curricula and we hope to encourage greater discussion on ethical data transparency from all disciplines, at these and other events.

If you are interested in learning about our short course opportunities, please visit https://arcticdata.io/training/.

References and further reading

Carroll, S.R., Herczog, E., Hudson, M. et al. Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR Principles for Indigenous data futures. Sci Data 8, 108 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00892-0

Puebla, I., & Lowenberg, D. Recommendations for the Handling for Ethical Concerns Relating to the Publication of Research Data. FORCE 11. (2021). https://force11.org/post/recommendations-for-the-handling-of-ethical-concerns-relating-to-the-publication-of-research-data/

Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group. (September 2019). “CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance.” The Global Indigenous Data Alliance. GIDA-global.org

Wilkinson, M., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, I. et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data 3, 160018 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18