Dr. Yoko Kugo is a recent Ph.D. graduate from the Interdisciplinary Studies Doctoral Program housed in the Arctic and Northern Studies at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Her research interests include place names, Indigenous and local knowledges, central Yup’ik language, Alaskan history, ethnography, cultural anthropology, and geography. She plans to continue to document and preserve Alaska Native cultural heritage, to apply Native knowledge to the management of natural and cultural resources, to teach younger generations to conduct social science research ethically in Arctic communities, and to help these Alaska Native communities strengthen their cultural pride.

Her dataset – Iliamna Lake (Nanvarpak, Nila Vena) Native and Local Place Names (2016-2019) – compiled the local place names in and around Iliamna Lake in Alaska with the help of five specific communities: Iliamna, Newhalen, Kokhanok, Igiugig, and Levelock. She considers herself fortunate to work with those communities to help them preserve their place names for the future.

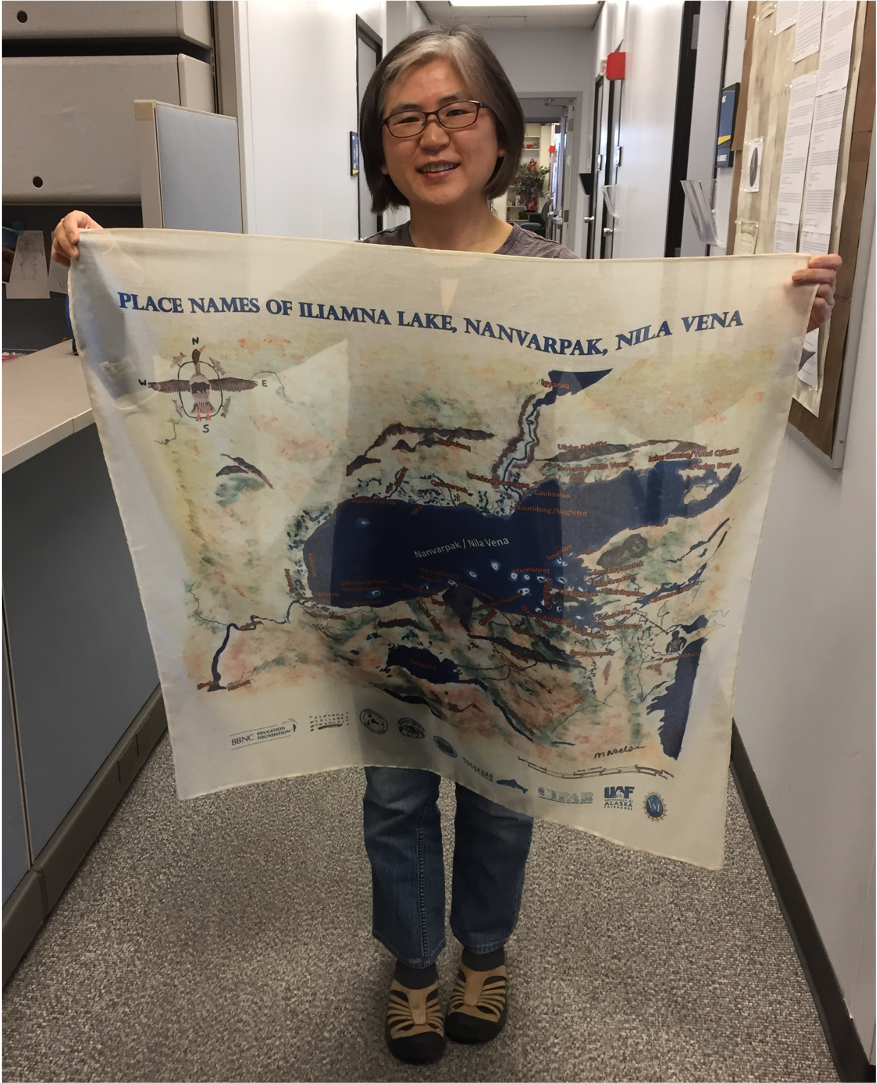

Dr. Yoko Kugo with her scarf depicting a map of Iliamna Lake with local place names. Photo Credit: Dr. Yoko Kugo

Check out the dataset and learn more about the importance and applications of this data in our Q&A with Dr. Kugo:

What research question does this project address?

This project was focused on making an atlas of Yup’ik place names in the Iliamna Lake area, noting how various places are named, of course, but more importantly how the place names have been used in the past and present by local communities for hunting, fishing, and travelling, telling stories, and enhancing their connection to the land.

Where did this research take place?

This research took place in the local communities around Iliamna Lake, which is the largest lake in Alaska. Multiple communities live around this lake and there was often more than one place name for a given location. For example, one community in the northeast part of the lake had one name for a place, and another community in the southwest had a different name for it – these groups see the various locations from different perspectives, and places are sometimes named using directions on how to get there.

What type of data do you collect, and how does it help you answer the research question?

I collected place names data using a community-based participatory approach, which means I spoke to 20 Yup’ik speakers and local knowledge holders through interviews and participating in community activities. I also held the Iliamna Lake Place Names Workshop that gathered 20 elders from 5 different villages together to share their stories and knowledge of the landscape in May 2018. It was an emotional gathering – the elders spoke about how they knew about the places (through their families or through local travel routes) as well as their memories, histories, and family stories of those places, with some being moved to tears. The elders were also able to learn the place names used by other communities from each other as part of this gathering. These are not just place names to them – they are part of the rich history of the land and the communities.

Can you share what the data are telling you so far?

Place names can be very solid data points from the “outsider” perspective, but to the local communities that I work with, the place names are changeable. The names are part of their memory, part of their map, part of their histories, and a part of their way of life.

What is one way your work is being applied to address issues in the Arctic?

One of the major issues facing the Arctic is climate change, and while my research doesn’t focus directly on climate change, place names often reflect changes in the environment. I worked with the elders using a United States Geological Survey (USGS) map to help identify the place names, and the elders would say to me that the place name denotes a place that no longer exists due to change. For example, a place name may contain references to a bend in a river that isn’t there anymore. Sure enough, when I investigated through Google Earth, I could see the change as well. In that way, place names can be a tool to see climate change.

Who do you think would benefit most by having access to your data?

Other researchers can benefit from my data, but what I’m more interested in is how communities can benefit from my work. It’s important to their way of life and their pride that their history continues to thrive – and remembering these place names is intrinsically part of that. The elders were happy to have all of this documented for them so that future generations will not lose this information or the connection with their past. Additionally, Alaska’s regional Native corporations can benefit from this data – I directed Bristol Bay Native Corporation to download my dataset from the Arctic Data Center, which was easy for them and for me.

What’s next?

I’m working with one of the local tribes in Alaska to write another proposal so that we can publish the Yup’ik place names in a book. The book will focus on the place names, of course, but will also be able to go more into depth about the stories around them, as well as provide pictures and references to the different elders and tribes that contributed their stories. That way, readers will know the stories in addition to the place names.

Citation: Yoko Kugo. 2020. Iliamna Lake (Nanvarpak, Nila Vena) Native and Local Place Names (2016-2019). Arctic Data Center. doi:10.18739/A2FX73Z6V