Whale Blubber Rendering for Energy

Bowhead whales are among the largest animals on earth, up to 20 metres (65 feet) in length and weighing 60 tonnes. They represent an immense storehouse of food and materials, including meat, bone, baleen and blubber, which was used for oil by Inuit since time immemorial, as well as by Europeans in the 16th to 19th centuries.

The successful hunting of so large an animal requires both great skill and an elaborate technology.

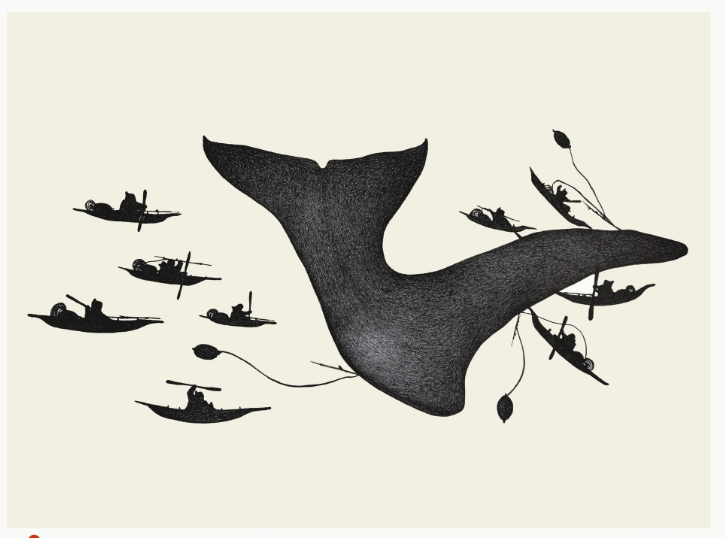

Traditional Inuit who hunted bowheads used a large skin boat or umiaq, and a heavy harpoon with a detachable head. When thrust deep into the animal, this detachable harpoon head twisted sideways, and could not be dislodged. Attached to the harpoon head by a long line was a collection of sealskin floats and drags shaped like buckets. These slowed and tired the animal as it swam. Harassed by a growing flotilla of boats, including kayaks, the whale eventually became too exhausted to escape, and was killed with lances.

Thule whaling communities were likely organized around whaling captains, known as umialit ("umiaq owners"). Membership in a whaling crew was based on extended family ties. In areas where whaling was particularly good, there could have been half a dozen whaling crews in a village of 50 or more winter houses. In prosperous areas, whaling captains were community leaders. In areas where whales were few, villages tended to be smaller and poorer, with a less hierarchical social structure.

Whaling was more than a practical union of skill and technology - it had spiritual aspects that were equally important. Inuit believed that animals have souls, which, if mistreated, could become bloodthirsty monsters. They also believed that animals deliberately gave themselves up to be killed by human beings. By treating an animal and its spirit with the proper respect, the good hunter ensured that he could continue hunting that animal, because it would be reborn to be hunted again.

These beliefs reached their highest expression in the various rules and rituals surrounding the hunting of the bowhead whale - the largest and most powerful animal of the Arctic seas.

The ancient beliefs and rituals of whale hunting are known from both archaeological evidence and Inuit oral tradition. Important beliefs and behaviours include the use of various songs and whale-shaped charms or amulets, to attract the whale and ensure its capture. Everyone on the hunt was quiet and respectful. All of the whaling crew members were careful to wear new, clean clothing, as a sign of respect.

After a successful hunt, the dead whale was offered a drink of water from a ceremonial bucket, beautifully made of baleen and decorated with whale symbols. Because whales live in salt water, Inuit believed they were always thirsty. The drink of fresh water was a gift to the whale for allowing itself to be killed.

Whale Bone Winter House

The long-abandoned village at Qariaraqyuk is located in a key whaling area in the Central High Arctic of Canada. It is the largest Thule village known, and its 57 whale-bone winter houses may have housed a population of about 300 people. Archaeological excavations revealed much evidence of whale hunting, including toboggans made of whale baleen.

People lived in the village at Qariaraqyuk between about 800 to 500 years ago, and then abandoned it for reasons that remain uncertain. Inuit bowhead whaling fell off sharply in most areas at about this time. Since then, Canadian Inuit have continued to hunt bowheads, but less systematically, often using kayaks rather than umiaqs.

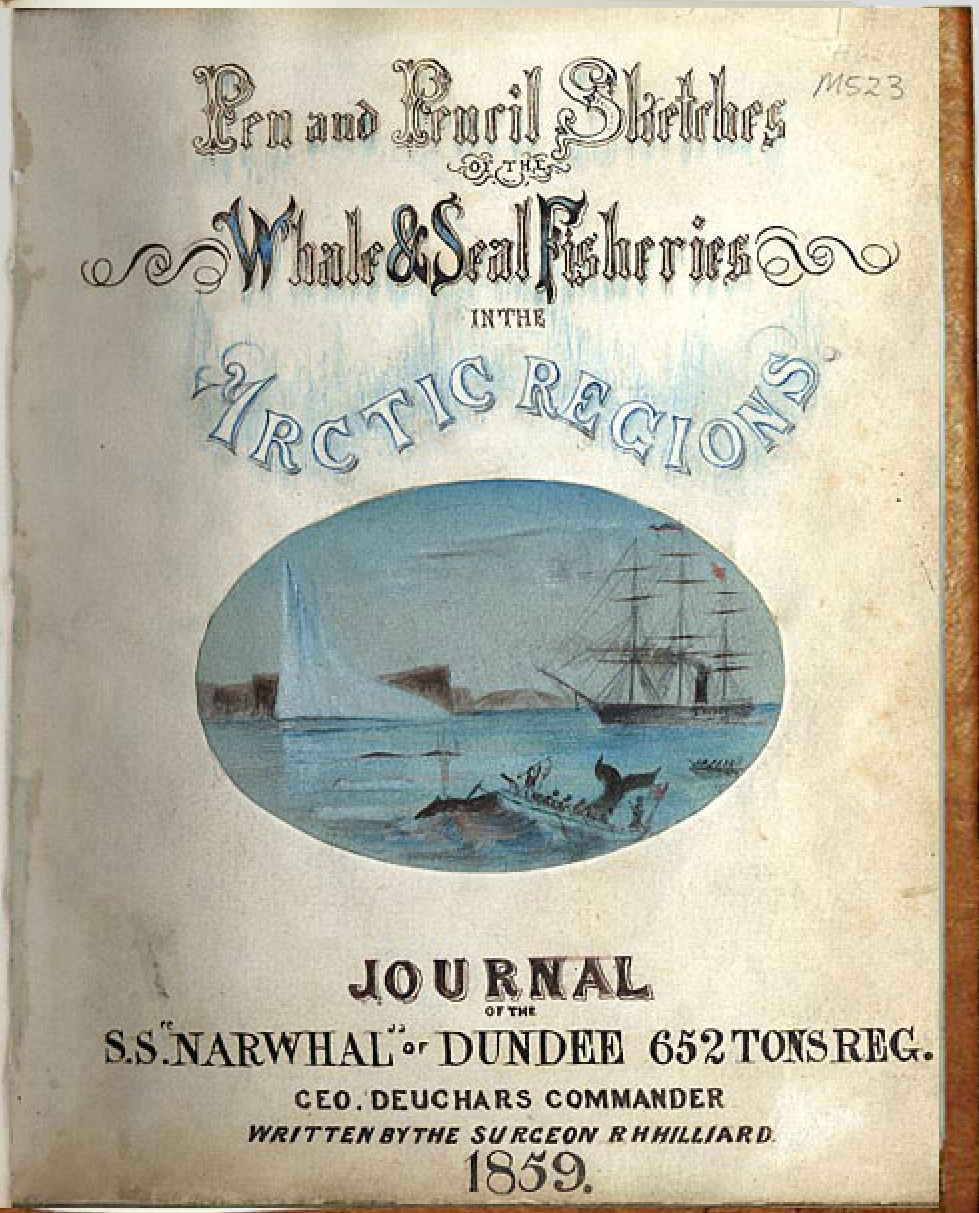

The Arrival of the European Whalers

By the 1500s, Basque whalers and fishermen were already working the Labrador coast and had established whaling stations on land, such as the one that has been excavated at Red Bay, Labrador. The Inuit do not appear to have been involved with their whaling activities.

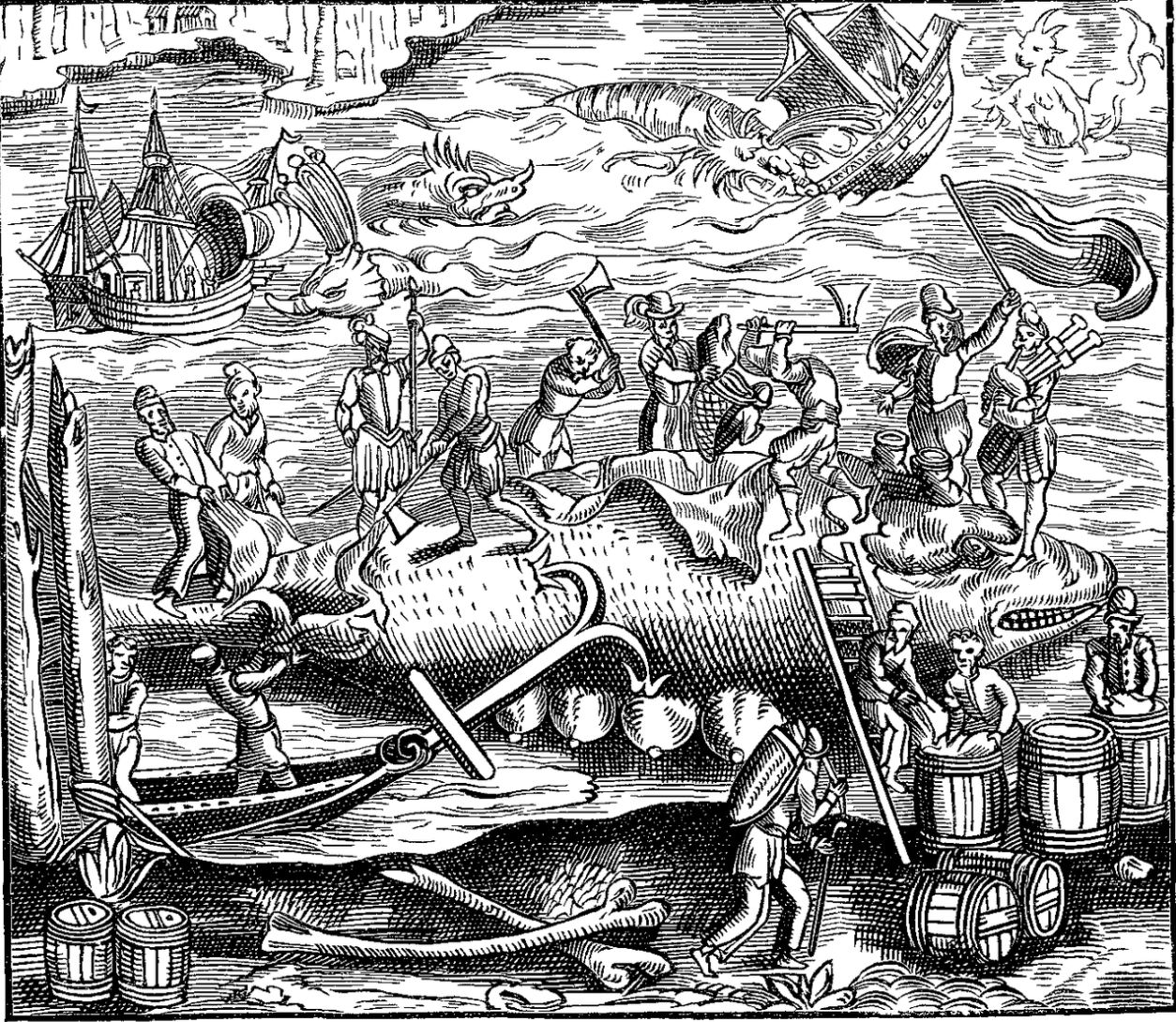

From the 16th century, Europeans began the move from a rural and agricultural society to a mixed economy that increasingly demanded artisans, craftsmen, skilled labour and movements from the country to city centres across Europe. One of the demands that came with their societal change was the need for fuel.

For centuries people had been rendering the blubber of sea mammals to create an efficient source of fuel. This demand sparked the whale hunting industry that put Europeans in the homelands of Inuit.

First European Encounters

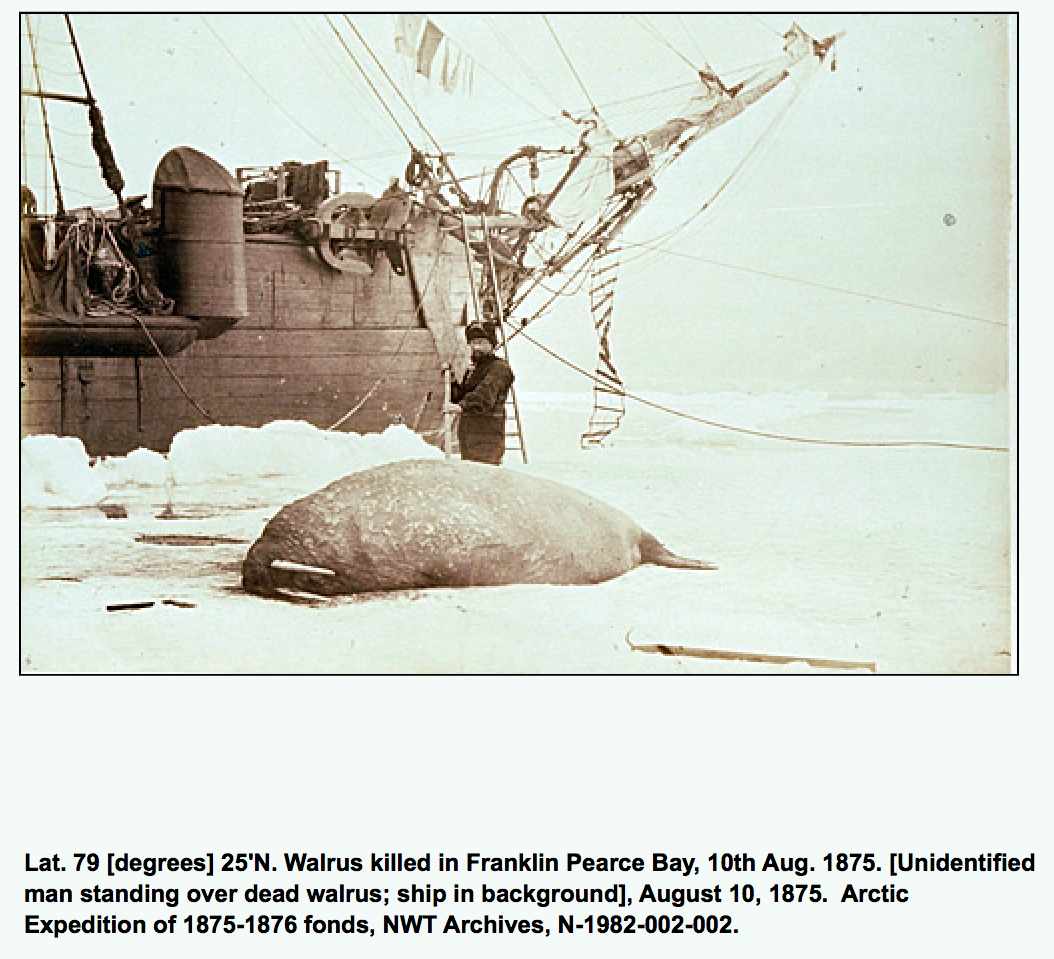

Inuit first encountered whalers along the Labrador and Greenlandic coast as early as the 1500's, but the whale hunt increased significantly throughout the 1700s and 1800s. By the early 1900s, the whale stocks were all but wiped out.

Over this period, as whales became scarce in some areas, whalers followed the supply into new areas. This brought whaling activity into the Hudson and Davis Straits, and then down into Hudson Bay. Whalers were looking for the supply of oil and baleen that the growing markets of Europe were demanding. At the same time, the Pacific whaling industry was moving North in the central Arctic coast and entered their activities around the Beaufort delta.

Both moves brought whalers into close contact with Inuit, and the whalers soon saw the advantage of employing Inuit in the industry.

Whaling stations were the first most established settlements of Inuit in these areas.

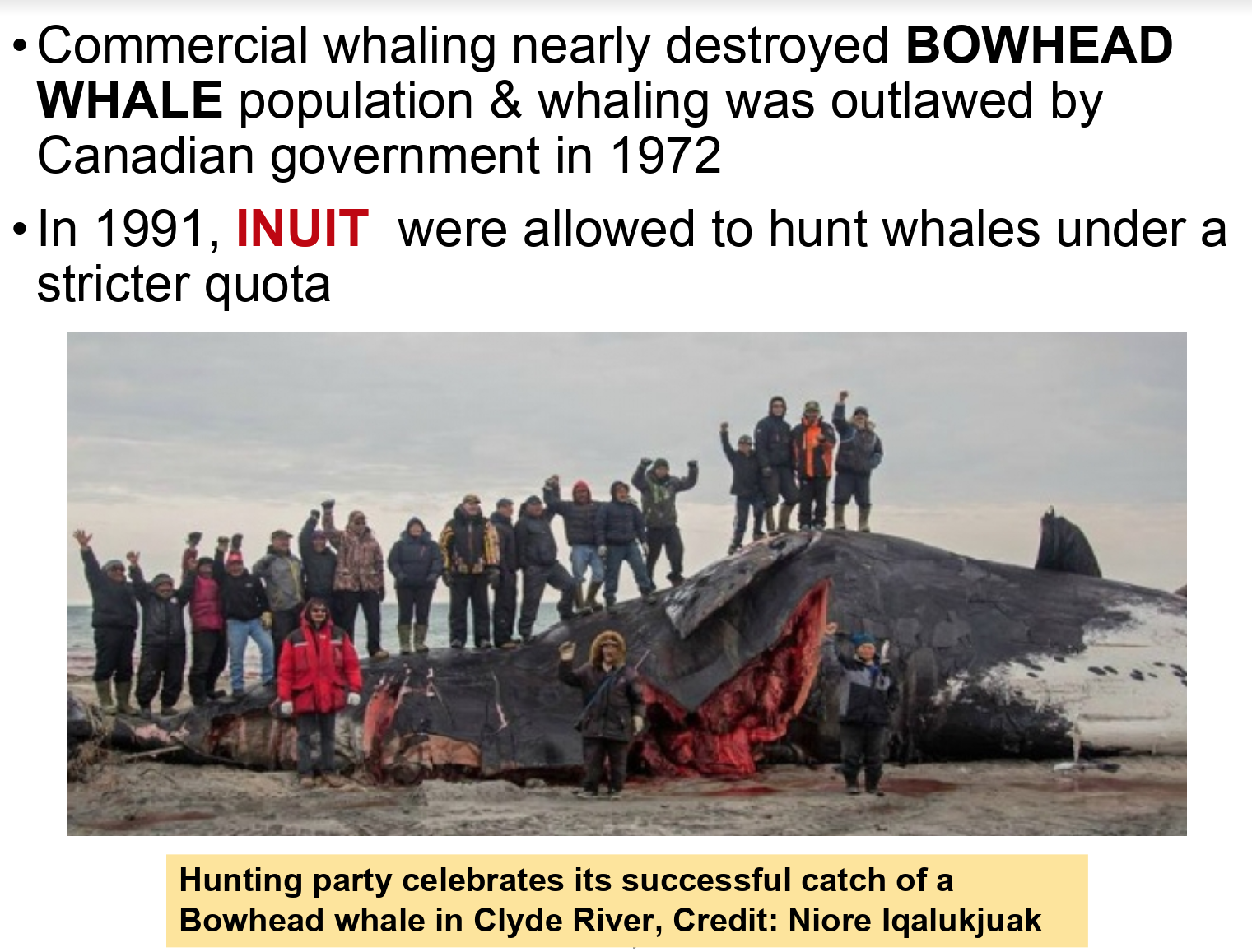

American and European commercial whalers had almost completely destroyed whale stocks in the Canadian Arctic by the early twentieth century. The traditional Inuit hunt lapsed, because of a collapse of whale populations and bans by government regulators.

However, by the 1990s, whale populations were beginning to recover, particularly in the Western Arctic. Eager to renew the important spiritual bond with the natural world which whaling represents, and Inuit are actively engaged in their cultural hunting practices and right to hunt whales.

Although hunts are few in number, they have great symbolic importance - the reassertion of a political right and an ancient spiritual connection.

Copyright © All Rights Reserved