Relocation to Permanent Structures

Inuit homes had a specific relationship to the land—they came from it and they were part of it. Nobody in particular owned the land or its resources, but they could achieve a measure of status from understanding it. In the new settlements, and in new houses, outsiders with almost no knowledge of the environment set out to completely redefine the relationship between Inuit and the land.

In this way, colonization became very real.

Before whalers and fur traders arrived, “home” for Inuit families was a broad geography where they were able to find or build everything needed to survive.

By the middle of the twentieth century, however, Inuit were expected to become part of an economic, political, and cultural system brought from the South that viewed shelter as a commodity that could be bought and sold.

Administration of the Arctic

In 1959, when the federal government outlined the Eskimo Housing Loan Program, the speed at which change was about to occur in Qikiqtaaluk could not be anticipated. Housing was not a stand-alone issue for Inuit or governments. It was completely intertwined with other factors related to the in-gathering of Inuit into settlements. Surrounded by new technologies, business practices, social organizations, and political processes, Inuit had almost no opportunities to influence housing programs or the design of settlements.

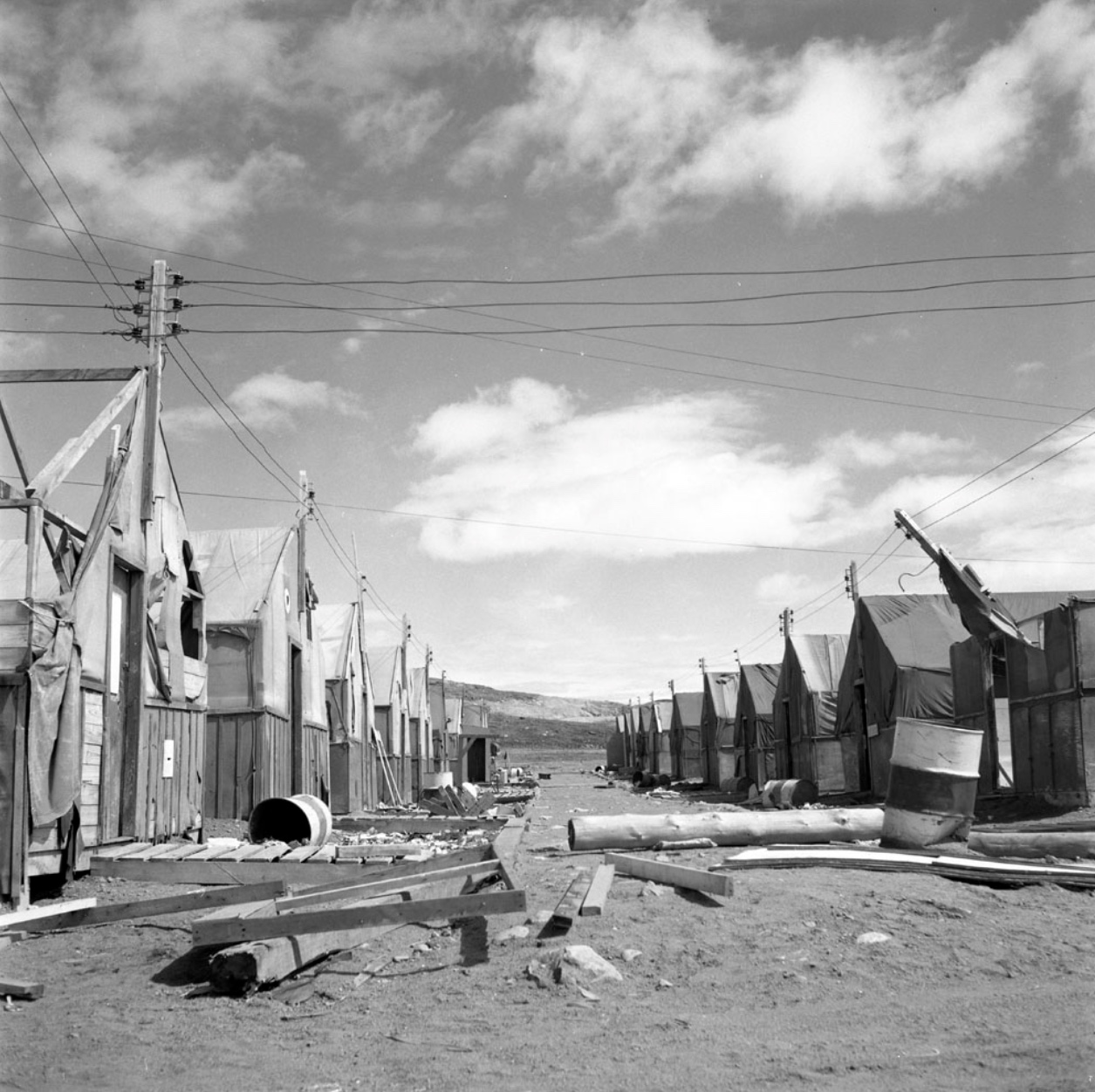

Source: National Library and Archives Canada dated 1960.

The federal government did not set out to harm Inuit, but it took advantage of the confusion by implementing programs that met their own objectives first.

It was only in the 1970s, that Inuit were able to take more control over their communities and housing. During the intervening period, with the limited information available to them, they tried to choose the options that would be best for their families, both in terms of where they lived and the type of shelter they used.

Many Inuit did not feel “at home” for many years after moving into the government-sanctioned settlements and into permanent housing, but they never fully released themselves from the land they knew well, nor from the cultural practices that were performed inside houses. Anthropologist Hugh Brody noted that even after most Inuit had moved into settlements in the 1970s, they continued to live on the land for at least part of the year.

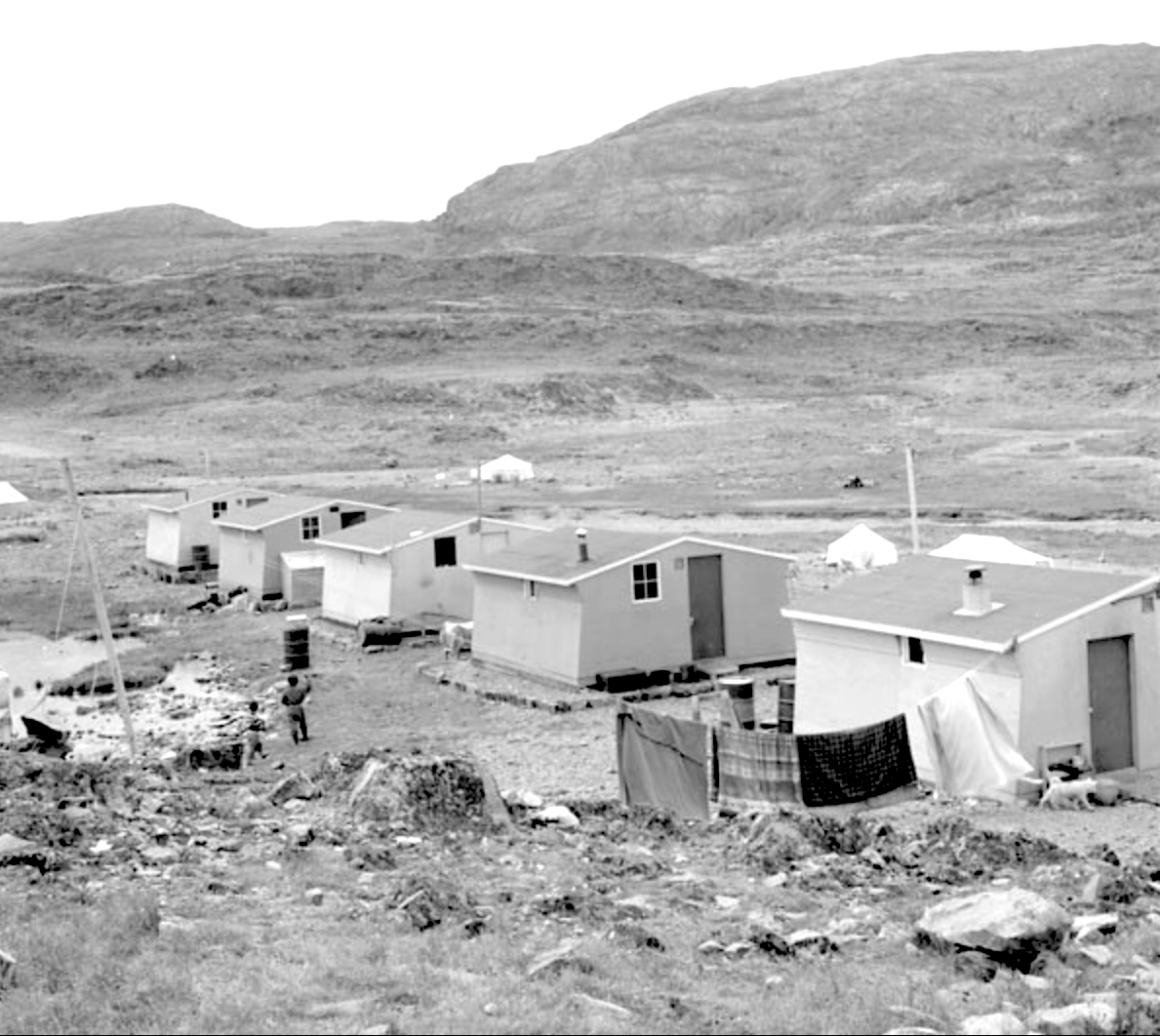

Source: This photograph is undated but is around 1955 in Frobisher Bay, NWT (now Iqaluit, Nunavut)

However much they may depend on rental housing in a government village, whatever their problems of isolation as the last to stay on the land, such men as the Inummariit still keep many or most of their possessions in the camp and try to spend as much time there as possible.

Inuit also continued to live in multigenerational families, and to share food, chores, stories, and laughter together in a single room.

During the second half of the twentieth century, the Canadian government increased its presence in Qikiqtaaluk to meet three key objectives: to demonstrate its sovereignty in the region; to prepare the North for the development of natural resources; and to address the wide differences in the kinds of services that were available to residents in northern and southern Canada. Inuit were enticed, and often coerced, to move to government-supported settlements for employment, schooling, and health services. Promises made by the government about the quality and cost of housing was an important factor in convincing families that it might be worthwhile to move into a settlement to be closer to children in school, to have access to potential employment opportunities, and to get more regular access to medical services.

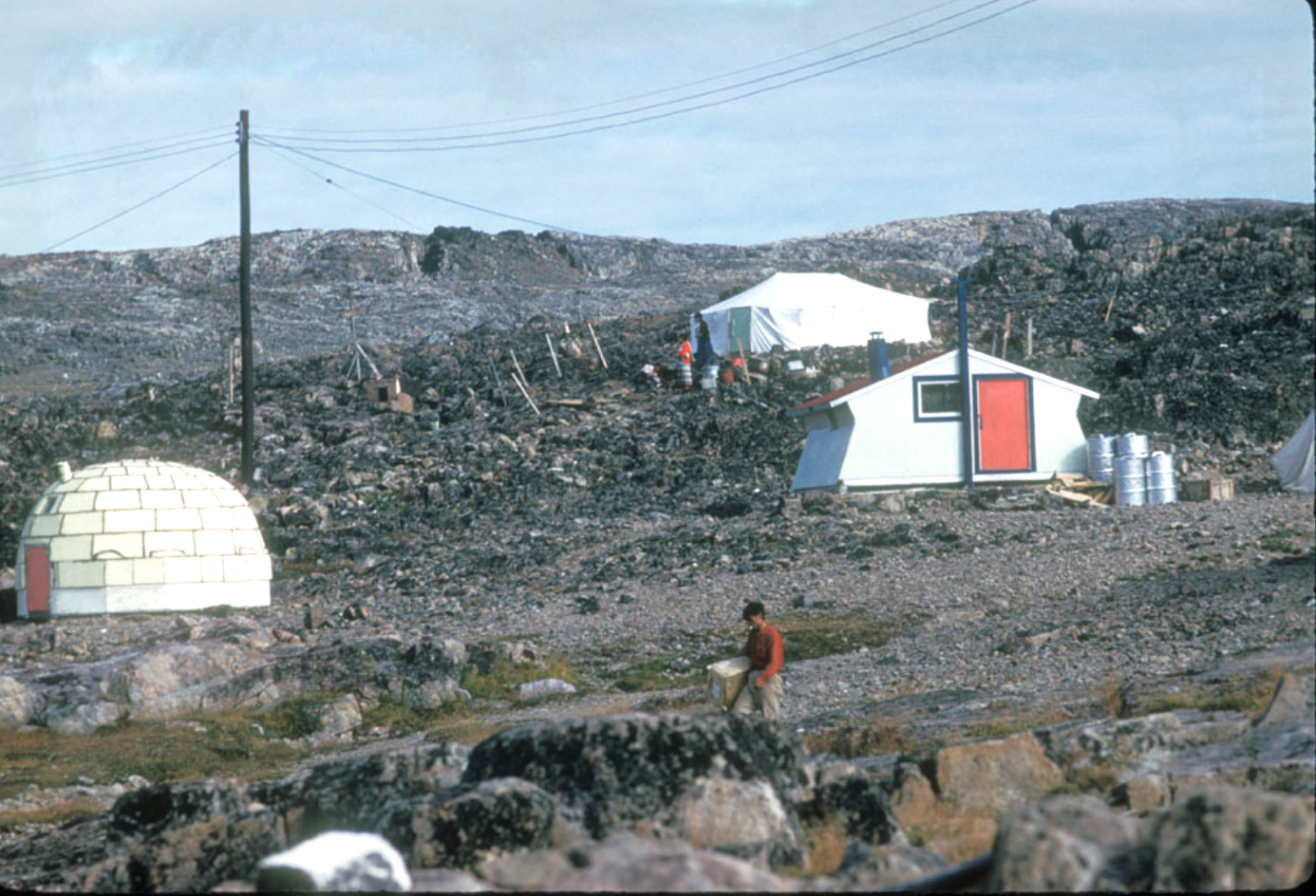

Bringing people closer to services was only part of the government’s rationale for supplying houses. The linking of new housing to both health and education remained central to the rhetoric of housing policy and pro- grams throughout the period, although the government itself put people at risk through inadequate preparation for housing. In one example, Inuit who had been relocated to Grise Fiord and Resolute were obliged to live in a tent in bitter cold because the snow was not suitable for building igluvigait.

By the early 1950s, in all parts of Qikiqtaaluk where military or government officials were to be found in any numbers, non-Inuit who were working in the North were consistently reporting that Inuit were winterizing tents by using scrap lumber for floors and reinforcing walls with wood, cardboard, and paper. Kerosene heating of homes left a residue of soot on the inside of houses and on clothes and bedding. When houses were crowded together, often near military bases, government officials and military personnel were quick to point out that health and sanitary conditions were being compromised. Good ventilation, low levels of humidity, and warm rooms were also noted as being essential to good health, and numerous sources advocated that houses equipped with both electricity and natural light were a necessity for families with school aged children.

Source: National Archives and Library of Canada. R12438-3904-4-E. Volume/box number: Dated 1956-60.

The precedent of providing housing to other groups of Canadians also played a role. During World War II, the federal government introduced a widescale housing program, commonly known as the Wartime Housing program, to accommodate the workers flooding into urban centres to work in factories. The prefabricated houses were small and designed with inexpensive materials so that they could be constructed quickly and cheaply. At the time, these designs were believed to be suitable for construction any- where in Canada. Wartime housing, which was also adapted for postwar programs, ranged in size from 600 to 800 square feet, included two entrance-ways and large windows.

Source: This photograph is from the Canadian National Library and Archives, but does not provide a date or location.

While government agencies touted the benefits to Inuit of living in new houses, the historical record and the material evidence show that programs were created to meet one government goal: to ensure that the costs of administering the North were as low as possible.

With Inuit living year-round in one location, it was easier to provide public services, especially schooling, and to bring Inuit into the wage economy.

Housing programs also served as a convenient way to teach construction and business skills, while also justifying investments in power and transportation infrastructure. The government discovered very quickly, however, that it was not simply a matter of building houses where services were available. “All the extras - medical services, welfare, social services, the wage economy, community conveniences - go with a house.”

Some Inuit welcomed and sought out opportunities to live in new houses. When anthropologist Toshio Yatsushiro interviewed Inuit in Iqaluit in 1958, after the first prefabricated bungalows or “matchbox houses” had been introduced, he reported that 75 percent of the interviewees said they wanted to live in one. Other families were less interested in government-provided housing, but felt pressured to move.

Source: This picture is of a styrofoam igloo; tent and prefab house with hydro, in Cape Dorset in 1960. The photograph is from the National Library and Archives, Canada.

Gamalie Kilukshak of Pond Inlet told the QIA, “They wanted us to have houses that were matchbox houses. Some of us didn’t want to get a house but they insisted. We were being pressured to get into a house so we complied. That’s what I remember. So we agreed to get into a house.”

The comfort of new houses, especially models that were larger and better constructed than matchbox houses, appealed to Inuit. Peter Awa told the QIA, “We were told that we were going to live in houses, warm houses.”

Copyright © All Rights Reserved